As of December 17, I have read 135 books this year. I write the titles of these books on paper, in the back of my 2023 planner. I like to keep the list on paper. I’ve come to enjoy looking back and watching my pen colour and handwriting change over the months.

I have this memory of being a kid and feeling a sudden panic about the sheer amount of books there were in the world—how could I possibly read everything I wanted to read? And what if the more I read, the more information I lost? I was already forgetting things about the books I’d read! If only I could keep track.

I decided to make a list of every book I’d ever read. I was only like 9, I figured, so I could probably remember every book I’d read in my short life. I decided to work backwards, starting with the book I’d just finished. (Oddly, I still remember that it was I Am The Cheese by Robert Cormier.) Then I recorded all the titles in my library stack that I had finished. Then I began to panic, because I couldn’t remember what I read before that.

I quickly abandoned my list, overwhelmed by the futility of trying to capture everything. But freeing myself from the need to preserve, listing becomes something else, some kind of memento, a marking of time. One thing I love about reading is the physical, durational aspect of turning pages. Reading contains the unique experience of occupying an internal world—built collaboratively by the words on the page and your own imagination—and at the same time be sitting in or moving through the real world, hearing the sounds around you, remembering to get off the train at your stop. When I look through my list, certain titles jump out at me: I remember where I was, how I was feeling, when I read them. I remember what I was thinking, what the words of the book sparked in me and where my mind was tending to wander as I read. What was preoccupying me. How much I was absorbed by the text.

It’s not as quantified of a year-end wrap up as Spotify wrapped, but I learned a lot looking back. January 2023 feels so far away, and yet I can’t believe it’s almost 2024. A year is a short and a long time.

My thoughts on the first half of the year seemed to have some common themes, and also turned out very long-winded, so I’m doing this in two parts. Stay tuned for the rest, providing I don’t go full holiday mode next week and completely forget about it!📚

JANUARY

The Magical Language of Others by EJ Koh / They Said This Would be Fun by Eternity Martis / Bliss Montage by Ling Ma / My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jenn Shapland / Shame by Annie Ernaux / So Sad Today by Melissa Broder / Nishga by Jordan Abel / Superfan by Jen Sookfong Lee / The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992 by Tina Brown / Winter in Sokcho by Elisa Shua Dusapin

I should write a diary, I thought. How amazing, to be able to look back on your life with such precision. Of course, I wouldn’t be swanning around 1980s New York, trying to avoid being sat next to Donald Trump at dinner parties, so my diary might be less exciting than Tina Brown’s.

I tried writing a few entries, but they all turned into meditations on pain. I’d been reading Brown’s hefty collection of diary entries while spread out on the couch under a heated blanket, chest burning and throbbing. For months I’d been having these attacks of chest pain that fit nearly all the symptoms of a heart attack but, according to the very nice paramedics that came to my house, were not. I was glad about that part, but was not adapting well to near-constant pain. It was strange to realize that, without realizing it, I’d been thinking of myself as a “healthy” person. It was sobering to realize that feeling limited by my body was a new thing for me.

And here was Tina Brown deep in the thick of New York high society, watching the money flow and flow and then suddenly dry up. Must be nice. I couldn’t stop reading the book. It was part escapism and part masochism. Every time my partner walked in the room I’d yell something about how Conde Nast used to send limos for their editors every day, and at every magazine job I’d ever had I had trouble wrestling even a taxi chit out of the budget.

I was writing so much about pain in my diary because I was becoming obsessed with my inability to remember physical pain in a visceral way. Even know, when I think back, I know I was in pain, but I can no longer recreate the sensation within myself well enough to even describe it. The next month we would go to New York; I would have a particularly bad attack of chest pain the night before but fight through it anyway. I remember thinking, when I think back and remember this trip, I won’t remember how terrible my body felt. And it’s true.

FEBRUARY

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi / The Incident Report by Martha Baillie / Glaciers by Alexis M. Smith / How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo / The Myth of Persecution by Candida Moss / Hotel Splendide by Ludwig Behelmans / If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga

But if I think hard, I can remember it—at least, I remember lying over the cylindrical pillow on the hotel room bed, trying to use it as a substitute-foam roller for my physio exercises, remember feeling too sick to ingest more than hot tea and a single soup dumpling at the first restaurant we went to.

It was reading week, and I ignored my homework in favour of Hotel Splendide, another form of New York escapism, this time from the 1920s. Halfway through the book, I realized the adventures of these heightened, wacky characters were not a novel, but a memoir of Behelmans’s actual job as a waiter at the Ritz.

Our hotel seemed to have been last renovated somewhere between Behelmans’s and Brown’s respective New Yorks. It had a creaky elevator with a metal door and wood-panelled walls, ornate-but-worn overstuffed armchairs in all the rooms and paintings of horses on the walls. It had recently been acquired by a hotel chain that put its name over everything but made no other alterations.

Behelmans’s New York—outside of the bubble of the Ritz’s dining room; even in the Ritz’s kitchen—had grit, and character, and that’s what seems to be seeping out of cities as high priced development moves in. I read about the backrooms of the Ritz and the strange characters that populated them while sitting on a Central Park bench, then while drinking a $6 latte at Blue Bottle on a freezing aluminum chair. The streets were beautiful and cold. Hot grease steam rose off our pizza slices. We stood in line at The Strand for 20 minutes when their POS system went down, just so I could buy an Edith Wharton collection I’ll never get around to reading. “When you buy a book in a city, it has to be thematically relevant,” I told Jon. They did not agree, and bought a copy of Watchmen at a comic book store. We drank the best vermouth I’ve ever had at Wildair. Tried to fit our knees under the table at a terrible tourist deli.

Behelmans put glamourous hotels in my head. I resisted visiting his mural at the Carlyle, where a single Old Fashioned costs $34 USD. But I kept gazing longingly at the Plaza. “Why don’t we get breakfast there?” Jon asked. I made half hearted arguments about our budget and then let myself be convinced. On our last day in New York we drank coffee out of china cups and ate the world’s most expensive croissants. A very Hotel Splendide server winked and recommended the freshly squeezed pineapple juice. I went to the bathroom in that famous pink bathroom. Behind Jon was a lady who belonged in an Eloise illustration, who was sitting at a table for one with a little dog in her purse. Everyone else in the room was either a businessman or a family wearing performance activewear, but she seemed to really belong there. She ordered coffee and caviar, which arrived in its little tin on top of a tiered tray.

MARCH

On Writing and Failure by Stephen Marche / Ducks by Kate Beaton / Fierce Attachments by Vivian Gornick / Shortcomings by Adrian Tomine / I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai / I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You by David Chariandy / All the Lovers in the Night by Mieko Kawakami / Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera / Sphinx by Anne Garréta / Saving Time by Jenny Odell

What I remember of March is spending my whole life on the TTC. Twice a week I’d take a bus up to the subway, ride the train to the end of the line, and take a bus to the Humber College north campus to attend workshops for my MFA program. This whole journey took about an hour and a half each way.

While I was doing this, I read. Hurtling through a dark tunnel while slowly flipping pages.

Anne Garréta was part of the Ouilipo movement of French writers who embraced constraint (though she joined after writing Sphinx). She wanted to write a book with no gender markers for its characters. She did this while writing in the 1980s, before a language around gender fluidity had solidified, and also writing in French, which has gendered adjectives. In French, even if you avoid using a pronoun, most adjectives and some verbs applied to the character in question would be conjugated according to that person’s gender.

The translator of the book made an effort to mimic Garréta’s sentence construction in French when moving the text to English, to help call attention to this effort. The translation also had to deal with the fact that in French, a possessive is gendered by the object being possessed, not the possessor; where in English one would say “his arm” and “his hand,” a French man’s arm would be son bras (masculine) and his hand would be sa main (feminine). This was convenient for Garréta but made for some backwards-sounding sentences in English. The resulting focus on the body, though, makes the book—which is a love story—very sensual. “The narrator talks about A***’s [the lover’s] skin, arms, shoulder, scent, […] mass of hair, curved neck, so that the adjectives agree with the gender of that particular body part in French,” the translator wrote:

A*** is also referred to as various nouns, including a spirit, a being, an other, a beautiful creature, a strange character, a phantomlike spectre, a vision, a funereal existence, a cadaver, a living cadaver, a life, a body, a beloved body, an inanimate body, an ephemeral body, a parasitic body,1 so that the adjectives agree with these nouns […]. Sometimes A*** is missing from the sentence altogether where there would normally be an object [… as in,] “I was surprised to find myself desiring, painfully.”

I found myself becoming more drawn to the negative possibilities of constraint in art. I wondered if the contemporary voice leaves too little interpretive space. There is something ghostly about A*** and the narrator in Sphinx. The extratextual material frames the book as withholding the characters’ genders from the reader (as opposed to exploring genderless characters)—I wonder if that was really Garréta’s aim? If so, this implies a distancing from the reader. But the book moved me more than I expected. I cried at the end, right there on the TTC. Or at least, had to blink really fast for a minute and tilt my head back. On the College streetcar, that time, going to get a haircut or something. I was thinking of that spectral body, beloved body. Outside, the slowly-melting snow was shrinking into hard, icy clumps.

APRIL

February by Lisa Moore / The Fake by Zoe Whittall / Exit West by Mohsin Hamid / Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles / Sacred Country by Rose Tremain / Natural Causes by Barbara Ehrenreich / Hazardous Spirits by Anbara Salam / Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng / The Furrows by Namwali Serpell / Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor

Another spectral book, one about not knowing what is real. My chest pain kept subsiding for a few weeks and then coming back. I kept having heart attack symptoms with no heart attack. My body seemed like it was playing cruel jokes on me. Every time I thought I figured out what was causing it, it would change slightly. My doctor got me to wear a giant medical-instrument-beige heart monitor under my clothes for 48 hours, “just to make sure.” She sent me out for blood tests and ECGs and more blood tests. “Everything looks good,” she’d say every time. This was less comforting each time.

In The Furrows, the same death keeps occurring—the death of the narrator’s younger brother while under her care—but the circumstances keep changing. There are gaps, skips and stutters of memory and perception. And where is the body? Is he really gone, or will he return, decades later, in a coffee shop, meeting his long-lost sister by chance? Did the tide take him, or something more sinister? Reality shifts so many times there never seems to be a “real” story, it all exists at once. The emotional reality carries through.

I’d never before had the kind of anxiety that spiked my bloodstream when I would start feeling the pain in my chest. I’d become convinced immediately that I was going to die. I had to talk down my own brain—remember how the doctor says everything looks fine? I kept having what in retrospect I think were low-grade panic attacks.

But then, miraculously, the pain would life for days or even weeks, and suddenly it was like it never happened. That same animal part of my brain is convinced I will never be in pain again—I’m cured!—a supersized version of forgetting the pain.

MAY

Little Labors by Rivka Galchen / Dumbshow by Fawn Parker / Unearthing by Kyo Maclear / Mennonite Valley Girl by Carla Funk / W-3 by Bette Howland / Bad Cree by Jessica Johnson / A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk

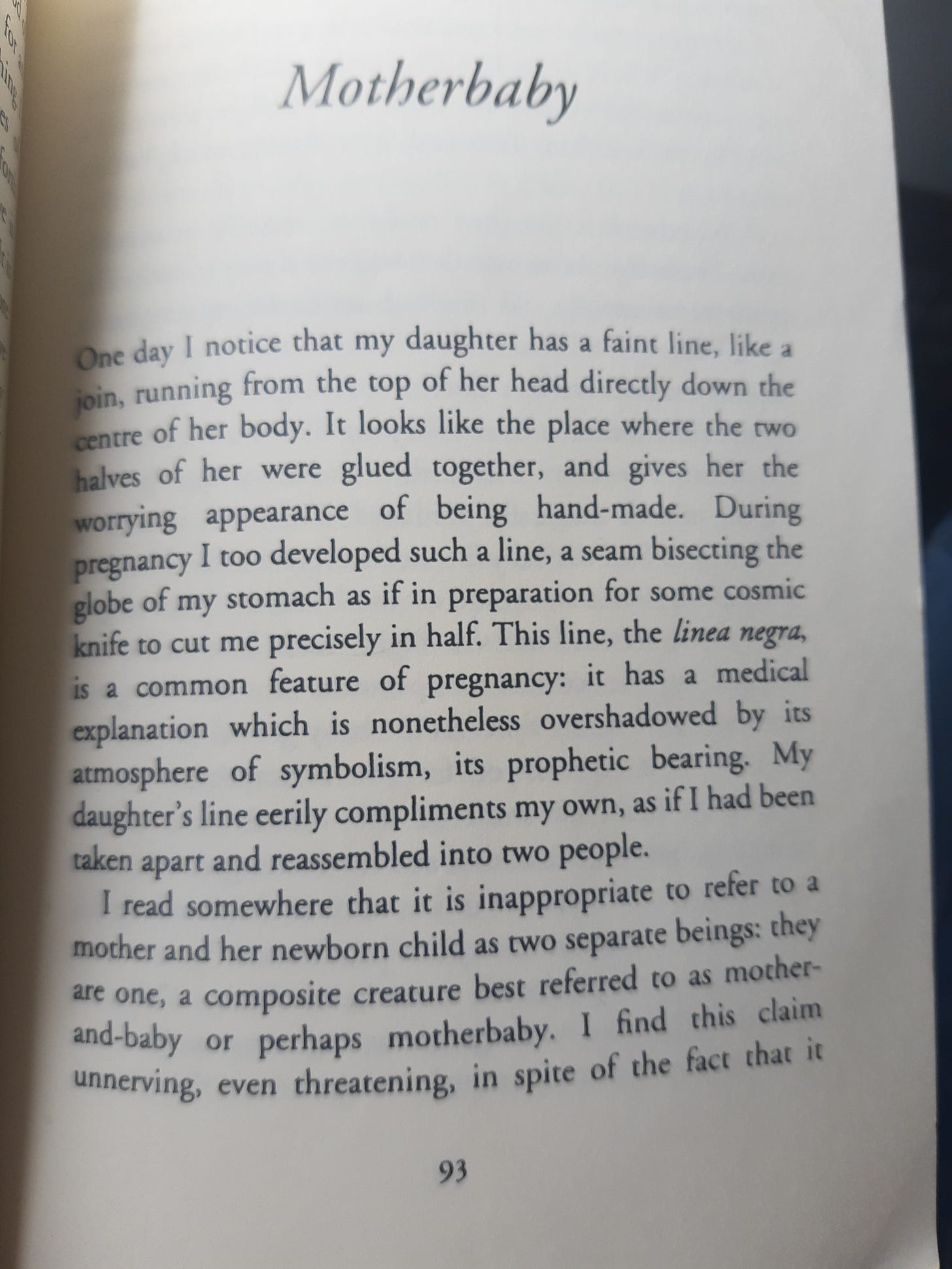

I was writing a novel about mothers and babies, on my way to visit my friend who had recently become a mother, to see her new baby. The book is also about travelling through time (in both the realistic and speculative sense). I was reading Rivka Galchen’s little yellow book on the plane. I underlined the sentence: We know babies are the only ones among us in alliance with time.

My friend’s baby was so tiny, cute in that alien way, bulbous eyes in a big bobblehead. She opened her mouth at me and sucked on my thumb. We pushed her hands onto an ink pad and pressed them against a piece of paper, to commemorate her smallness.

I know that the mother’s and the child’s cells intermingle, that we contain parts of each other long after our bodies divide. My friend told me that for the first few weeks or months, a baby won’t smile at her mother, because she believes they are still the same person. I immediately made a note to put this in my novel. Later, when I googled to see if I could find out more about this, I came across this horrifying sentence on an Australian health website: “By six to nine months of age, your baby begins to realise they are a separate person surrounded by their own skin.”

Galchen’s book returns over and over to the baby as potential, the child who is a mystery to her mother, who is growing and changing in every moment. “Oh,” she realizes, “children are pregnant with themselves.”

JUNE

Dear Scarlet by Theresa Wong / The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt / The Overstory by Richard Powers / Thrust by Lydia Yuknovich / The Gentrification of the Mind by Sara Schulman / Sodom Road Exit by Amber Dawn / Pray for Us Girls by Cara Nelissen

After a month and a half of feeling good, my chest pain kicks up again. My doctor tells me I should go to the emergency room to get the tests done when I’m actually feeling it. I spent six hours in the ER, being moved from tiny room to hallway to different tiny room to foyer. In the meantime, I read almost the entirety of The Gentrification of the Mind, which is the only thing I’d brought with me, not realizing that spending six hours in a busy hospital reading about the destructive legacy of AIDS might not be the best move, mental-health wise.

Schulman argues that our activism and our thinking have been gentrified, that the post-AIDS generations have a passivity, an unwillingness to agitate for what we need, are too willing to view our rights as gifts. I see myself, unfortunately, in some of her illustrative examples, though I also think I see a shift away from this mode since the book was written in 2012. Other waves of disillusionment have hit the shore since then.

Across from me in the ER waiting room that night were two police sitting on either side of a young white man with a bruised head. He seemed to be waiting to be scanned for a concussion. His wrists were zip-tied together. One of the cops kept talking to him about how he could work on himself, learn to control his rage, not give up. The man kept bemoaning that they wouldn’t give him a cigarette. “You want something? One of us could run and get some food for you, if we have to wait too much longer,” the talkative cop said. The man reminded him they’d already gotten him a sandwich earlier. “How was that, by the way?” asked the cop. “Was it a good sandwich?”

“Was it a good sandwich? What—quit trying to make fucking conversation with me, man. It was a sandwich, whatever. I’m supposed to be so grateful to you for getting me a sandwich. I need a smoke.” He turned to the other cop. “I know you have smokes, I saw your lighter.”

“I swear, I don’t have any smokes,” said the other cop, grumpily.

There was an uneasy silence. After a while they started up talking again and eventually the guy started thanking the cops. “You’ve been nice to me, I know you didn’t have to be so nice to me, man.” I wished they wouldn’t make him sit there with his hands tied like that.

On the other side of me, a nurse complimented an older Black man’s Obama 2012 baseball cap while checking his vital signs.

“You know, I met Obama,” the man said conversationally. “I shook his hand.”

“What?” asked the nurse. “Are you serious? How did that happen?”

“I was in Chicago,” the man offered simply, and then fell silent.

Eventually I was, again, told by a cheery nurse that “Everything looks great!” and exasperated, I said, “I feel horrible, though.” She apologized and asked me where I got my tote bag. She liked the design.

But in the end, it worked out. I’d been trying an acid reflux medication for my stomach, and the ER doctor prescribed me a stronger one, and in the next few days, it worked. The chest pain went away. A displaced pain, it turns out—caused somewhere else but not felt until it rippled outward. I finished Schulman’s book when I got home that evening. It's a bitter pill to swallow, she wrote, but the people who make change are not the people who benefit from it. 📖

Writing News

I don’t have any new writing to share until the new year, but in positive news, I found out I’ve received a Recommender Grant for one of my writing projects through the Ontario Arts Council! (Yay!)

If you are a writer and live in Ontario, I highly recommend applying for these grants. (The deadline is in mid-January!) The application is fairly simple and while the money comes through the arts council, your project is recommended for funding by the local publishers you submit to. So it’s a nice boost and a good way to gauge some interest in your work. (If you have questions about it let me know!) Info here!

Other Links

It’s almost the holidays, which for me (coming from a Mennonite tradition) is really meant to be a time of peace. I thought I’d make a short list of some actions towards peace that I’m interested in this season, to share—and I’d love to hear more ideas!

December 18 is a national day of action for Palestine. If you live in Toronto, there are several community actions at different MP offices around the city—here’s a post that collects them all. There is also a vigil scheduled in remembrance of the more than 18,000 killed in Gaza.

Also speaking of Gaza, without a ceasefire, aid organizations have no way to deliver help to those who are wounded and starving. (Mennonite Central Committee, the religious relief agency, wrote quite a well-worded post about this recently, I thought.) Without the option of aiding humanitarian relief, I think it’s important to continue direct political action like emailing representatives and showing up for protests to demand a ceasefire. Community Defense Funds also need donations.

Congo is also experiencing massive violence ahead of its election later this month, and the UN reported earlier this year that a record 7 million people have been displaced. Some of this is driven by cobalt mining. The UNHCR could be a good option for a direct donation. It’s also worth meditating on the invisible impacts of the technology we use daily.

I love the work that Community Fridges Toronto does in helping communities fight food insecurity in a grassroots way. They have a fundraiser on right now to maintain and winterize their fridges and pantries.

Also because it’s nearly Christmas: Sufjan Stevens has a nearly 5-hour long Yule Log video with all his Christmas music playing in the background. Highly recommend. 🎄

Tag yourself, I’m a funeral existence.

As the kids would say, 'relatable content'. And being "overwhelmed by the futility of trying to capture everything" regarding books is a perennial feel over here. Tagging myself as a living cadaver.