My Year In Books: Part Two

Apparently it is now 2024.

I slid slowly into 2024, like wet slush rolling off a roof. I’m still writing 2023 everywhere. I think at midnight on new year’s eve I was brushing my teeth in my parents’ bathroom. An auspicious start to the year. My partner and my dog and I drove two days to get home from holidays in Winnipeg, stopping at every Love’s gas station from North Dakota to Michigan. I love Love’s, which not only has every flavour of International Delight creamer for your coffee (why do Americans love nondairy creamer so much?? A mystery for the ages) and other necessities like rhinestone-crusted pink camo baseball caps, it prides itself on having particularly clean bathrooms. They really are the best bathrooms around. The stalls go all the way to the floor, and have that lock that tells you if it’s vacant or not. They’re always very clean and never out of soap. And they pipe country music right in there, always a different song that somehow sounds the same, which for some reason really enhances the experience.

After getting home, I thought I would write this newsletter and finish a draft of my novel, and instead I found myself lying on the couch watching the entire first season of Girls. I can’t remember why. Maybe for the schadenfreude of watching another writer struggle? But it just ended up making me feel old. Did you know 2012 was 12 years ago?

All this is to say, I’m moving slowly, but I suppose that’s okay. Writing through my list of books feels like it helps, giving some shape to the year that just passed. So far, 2024 doesn’t have the “fresh, new” feeling that I’m used to when a new year begins; things feel heavy lately.

But who says you need to wipe the slate clean? I’ve been thinking a lot about the value of maintenance and resilience. Jenny Odell writes in How To Do Nothing that our cultural conception of productivity “is premised on the idea of producing something new, whereas we do not tend to see maintenance and care as productive in the same way.” We tend to ignore, minimize the importance of ongoing care. I’m not very good at resolutions, but I hope to make maintenance and care a theme of my life this year.

Anyway, I’ve continued looking back at my reading this year, and picking out some moments that these titles reminded me of. If you’re reading this, I’d love to hear recommendations from your own 2023 reading and what you’re taking into 2024! Wishing you care and lightness in this slow, wet January.✨

JULY

I Love Dick by Chris Kraus / Sunshine Nails by Mai Nguyen / The Woo-Woo by Lindsay Wong Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Shamed a Generation by Linda Kay Klein / The Jesus Machine by Dan Gilgoff / Jesus and John Wayne by Kristen Kobes du Mez / Virgin Nation by Sara Moslener / Knocking Myself Up by Michelle Tea / I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith

After reading four books about evangelical Christian purity culture for book research, I decide to cleanse my palate by reading Michelle Tea’s infertility memoir. It’s a beautiful and very funny book about queer family-making. The other palate-cleanser in my book stack was Dodie Smith’s I Capture The Castle, which is a novel I somehow missed out on as a kid.

I packed Smith’s book in my bag when Jon and I went to spend our tenth anniversary in a ritzy hotel in Yorkville (day rate, baby!). I read it on the rooftop balcony, after doing two boring laps of the pool. I found it entrancing and imaginative. I love books from the early 1900s that have such a fresh and casual style, that still feel immediate.

From the corner of the balcony, we could see the tight rows of houses, pubs, and Pilates studios crunched between St. George and Avenue Road. I traced over the streets with my finger in the air, mapping out my newfound knowledge of 1960s hippie-haven Yorkville as acquired through novel research. This was all homes—that building wasn’t there—that was a cafe—that church had the drop-in centre—The average home price in Toronto this summer was $1.1 million dollars or so; I’d read recently the average one-bedroom rent in the city had topped $2,500.

In I Capture the Castle, the father is a struggling writer whose one well-regarded book has begun to fade into obscurity. The family is no longer able to live on the royalties, and with him producing no new work, are getting by in their castle in the countryside by slowly selling off their furniture and eating meager dinners in their icy, unheated home.

I likely would have found this tale of stoic English poverty romantic as a kid, but now I’m just jealous that their landlord died and they’re not paying rent on the castle. Then again, it’s possible to live well on little these days, in some ways—abundance is cheap, longevity is impossible. I can splurge on a nice staycation but if my landlord sold my building I wouldn’t be able to afford to live in this city. And I can’t even think about the writer father keeping his whole family fed on the royalties from a single book. It’s a weird place to be in in life, I’ll admit, to be jealous of a broke, fictional writer while sitting on the roof of a four-star hotel.

AUGUST

Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker / Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? by Lorrie Moore / Regretting Motherhood by Orna Donath / The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk / The Art Thief by Michael Finkel / On Women by Susan Sontag / Birds Art Life by Kyo Maclear / The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor

Lorrie Moore is one of those writers who changes my internal monologue. I feel like I notice more, see the world around me differently, express myself more fluently, through the duration of reading her. Until the book ends, anyway.

In August, I relaxed. I decided I would take a break from writing and researching for the month. I gardened, reorganized the living room. Had beach days and dinner parties with friends. Read at cafes, learned Muna songs on guitar.

From Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?:

“My childhood had no narrative; it was all just a combination of air and no air: waiting for life to happen, the body to get big, the mind to grow fearless. There were no stories, no ideas, not really, not yet. Just things unearthed from elsewhere and popped up later to help the mind get around. At the time, however, it was just liquid, like a song—nothing much. It was just a space with some people in it.”

August made me think of childhood. I like the in-between spaces where you’re waiting for life to begin. The month before school starts up again. The time between signing the contract and starting the job. Between getting the pitch accepted and delivering the draft. Awash in a rewarding kind of laziness, a purposeful aimlessness.

I have a quote from art critic Jerry Saltz pinned up above my desk. It’s a moment from his essay “My Appetites” in which he is describing his childhood:

“My life was fine. I spent days gazing at dust motes in sunlight, flipping over on my back to pretend the ceiling was the floor, and feeling whole other worlds in these things—all like some happy domestic cat.”

I’m not sure why this image struck me so deeply except that that feels like my own memory of my childhood—long days of draping my tiny self over furniture, staring at dancing dust motes, imagining languidly. Time is long, when you’re a child, and there is so much of it.

SEPTEMBER

Butts: A Backstory by Heather Radke / Bluets by Maggie Nelson / Kindred by Octavia Butler / Not That Kind of Place by Michael Melgaard / Odes by Sharon Olds / Syncope by Asiya Wadud / Dead Man’s Float by Jim Harrison / Bunny by Mona Awad / Wonder World by KR Byggdin

The theme of my MFA program’s plenary course this year was “Writers in the World,” and much of what we talked about were he transition points: how do writers absorb the world and translate it into their work, and conversely, how does their work enter back into the world?

I September I read all of Syncope, a reading on the course syllabus, in an afternoon, unable to stop. The book is, “a reckoning / a recitation / a dirge / an imprint” about the Left-To-Die Boat, an inflatable boat carrying 72 people fleeing Tripoli which ran out of fuel in the Mediterranean Sea in March 2011. Despite plenty of surveillance in the heavily populated waters and interactions with a military helicopter, the boat was not provided any assistance and 61 people died.

How can art cope with tragedy? Or not tragedy, tragedy is not pointed enough of a word. I suppose I mean cruelty.

When talking about writing the world it seems impossible not to invoke words like “reflecting” or “engaging with” or “exposing,” none of which feel quite right, quite integrated or visceral enough.

In the fall, I became obsessed with metaphor, particularly with its limits. This was birthed out of a presentation I had to do for class on Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem and Martha Baillie’s essay “Her Body.” I was struck by a section in Diaz’s poem “The First Water is the Body”:

The Colorado River is the most endangered river in the United States--

Also, it is a part of my body.

I carry a river. It is who I am: ‘Aha Makav. This is not metaphor.

When a Mojave says, Inyech ‘Aha Makavch ithuum, we are saying our name.

We are telling a story of our existence. The river runs through the middle of my body.

The insistence against metaphor in this case pinged something deep inside me, opened something up for me. I felt like I could understand more other ways of knowing than what I’d always been taught. I’d always thought of metaphor as inherently expansive, but here I could see how it functioned as something limiting—or how it could be a cudgel.

OCTOBER

And Then She Fell by Alicia Elliott / How To Blow Up A Pipeline by Andreas Malm / Rave by Jessica Campbell / Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz / Nothing Special by Nicole Flattery / Yellowface by RF Kuang / The Waiting by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim / The Circle by Katherena Vermette / The Candy House by Jennifer Egan / Bonjour Tristesse by Francoise Gazan

Another book I read in this time, not for school, also made me question what happens in the crossing between writing and reality and back again. I’m generally pretty catholic in my reading appreciation, but I found How To Blow Up a Pipeline to be a rare book that I actively disliked.

Malm spends most of the book decrying pacifism, and as a pacifist from a long line of pacifists, I found his weird strawman simplifications of the ideology lacking. Not least of which because he ultimately seems to be suggesting only that climate activists commit some light property damage or civil disobedience, neither of which the pacifists I know would have likely have a problem with. It’s not exactly The Anarchist Cookbook; despite the title, I found the book supremely unradical in its actual prescriptions. He waxes poetic about the glory days when he and his activist group would put lentils in SUV tires to deflate them, leaving notes on the windshields for the owners to scold them for their gas-guzzling vehicles. Whatever its merits, this hardly seems akin to blowing up a pipeline. I mean, they didn’t even slash the tires.

A reviewer for the Los Angeles Review of Books1 also noted the tilted view of his focus:

Disappointingly, considering Malm’s expertise on Iran and the occupied Palestinian territories, he focuses inordinately on protest in the Global North. Only in passing does he mention Indigenous activists who battled the police and temporarily shut down the largest pipeline in Ecuador. The European activist group Ende Gelände (translated from German as, roughly, “here and no further”) gets far more space in his book. For years, Ende Gelände has sent thousands of its members to disrupt operations in coal mines and fracking sites but it has not escalated its tactics nearly as aggressively as the Ecuadorean protestors did. An alternative focus would have revealed far more individuals engaging in the strategy Malm favors, even if these activists will never get the headlines XR or Greta Thunberg do. Certainly, his scattered references to such actions in the Global South end up troubling his three neat phases of climate activism.

Also troubling to me was his SUV-tire-puncturing activist group, which he remembered so lovingly, appropriating Indigenous identity as some kind of shorthand to aligning themselves with the environment—which, aside from minimizing the mammoth contributions of actual Indigenous groups around the world to slowing climate change also relies on a bunch of racist tropes about indigeneity. He gestures at a half-hearted apology toward this in the book, and then continues to use the metaphor of “Cowboys and Indians” throughout. Again, I thought, an example of too much metaphor—a metaphor that erases others, erases reality.

The “violence” he says is missing and necessary from contemporary climate movements is all metaphorical as well, in a way—property damage always acting as a metaphorical stand-in, property for people. Meanwhile, I feel this clash up against the literal; the violence we face from the climate crisis is all too real. Death, displacement, a ravaged earth.

NOVEMBER

Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces by Jenny Erpenbeck / The Fraud by Zadie Smith / There is No Blue by Martha Baillie / You Are Eating an Orange, You Are Naked by Sheun-King / Strip Tees by Kate Flannery / Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli / What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad / White Cat, Black Dog by Kelly Link / 77 Fragments of a Familiar Ruin by Thomas King

In November, the Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha was imprisoned by Israeli military forces; I, like many around the world, read his work, not knowing whether we were reading the poetry of a dead man. In January, The New Yorker will publish his full account of escaping Gaza, including the detention, horrifying, humiliating, dehumanizing, brutal. From a reference to his birthday in the article, I will learn that he is one year younger than I am. I will study the small picture of his face at the beginning of the article for a long time.

For my metaphor presentation, I’d read the first essay in Martha Baillie’s book There is No Blue. Reading the third and final essay, which comprises most of the book, I was struck by the beautiful care Baillie recounts in collaborating with her sister on a book called Sister Language. Baillie’s sister was shizophrenic, and Baillie describes her relationship with words, with her poetry, as completely unmetaphorical; to destroy any of her words was a literally violent act, one she felt as keenly as physical harm. While collaborating on the book, Baillie worked with the editor on her sister’s behalf. They were allowed to move or cut full sections of the writing, but not change anything within, not a single letter. The writing was in discrete units that could not be disturbed.

I thought of this later while proofreading, picking through the Chicago Manual of Style in an attempt to determine whether there should be a comma between a certain two coordinate adjectives or something. “This is not a metaphor”—there is something very powerful in that sentence.

DECEMBER

Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe / The Dyzgraphxst by Canisia Lubrin / Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman

I only read three books in December, but they were a beautiful triptych; I read them slowly, savouring.

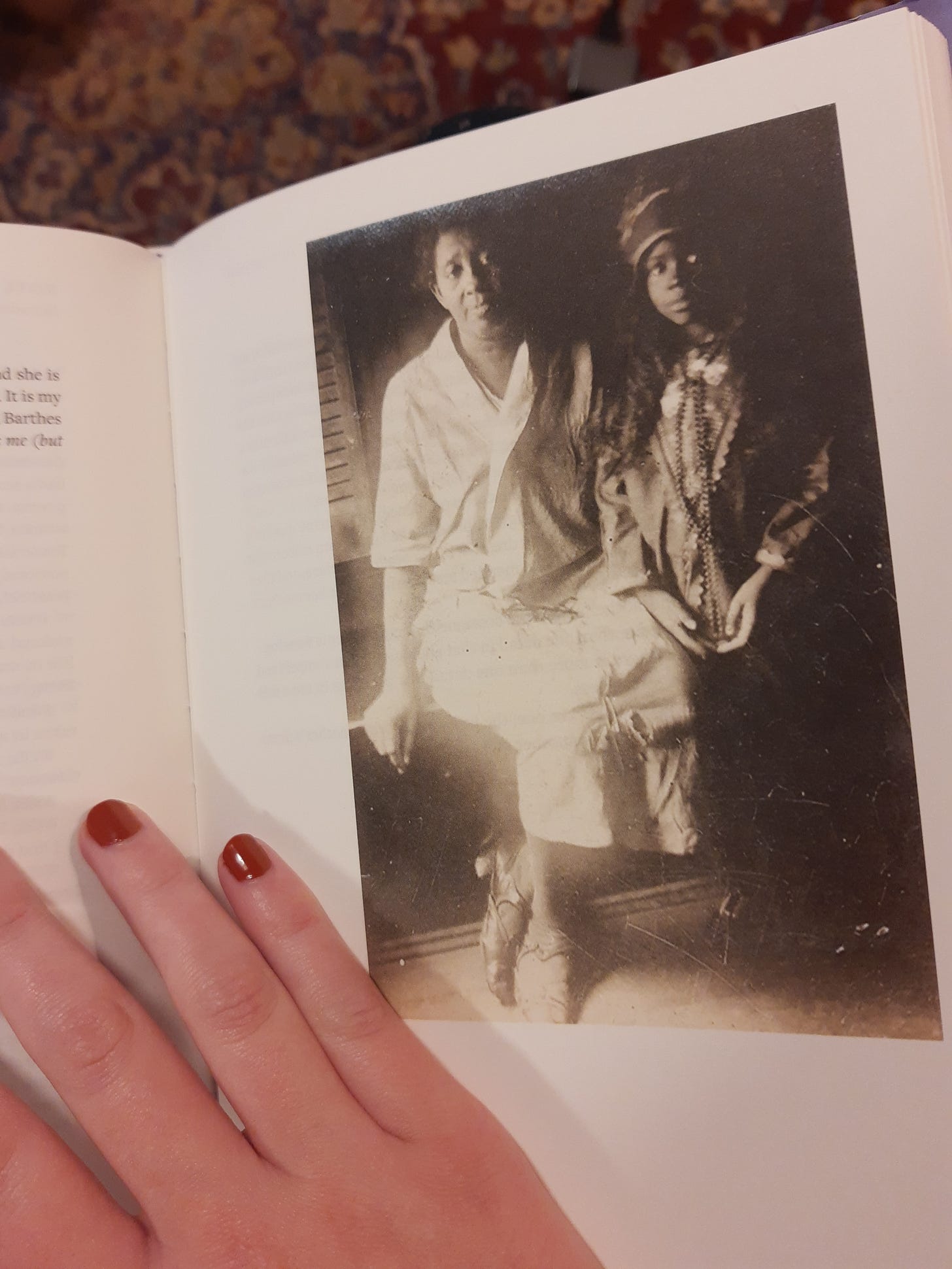

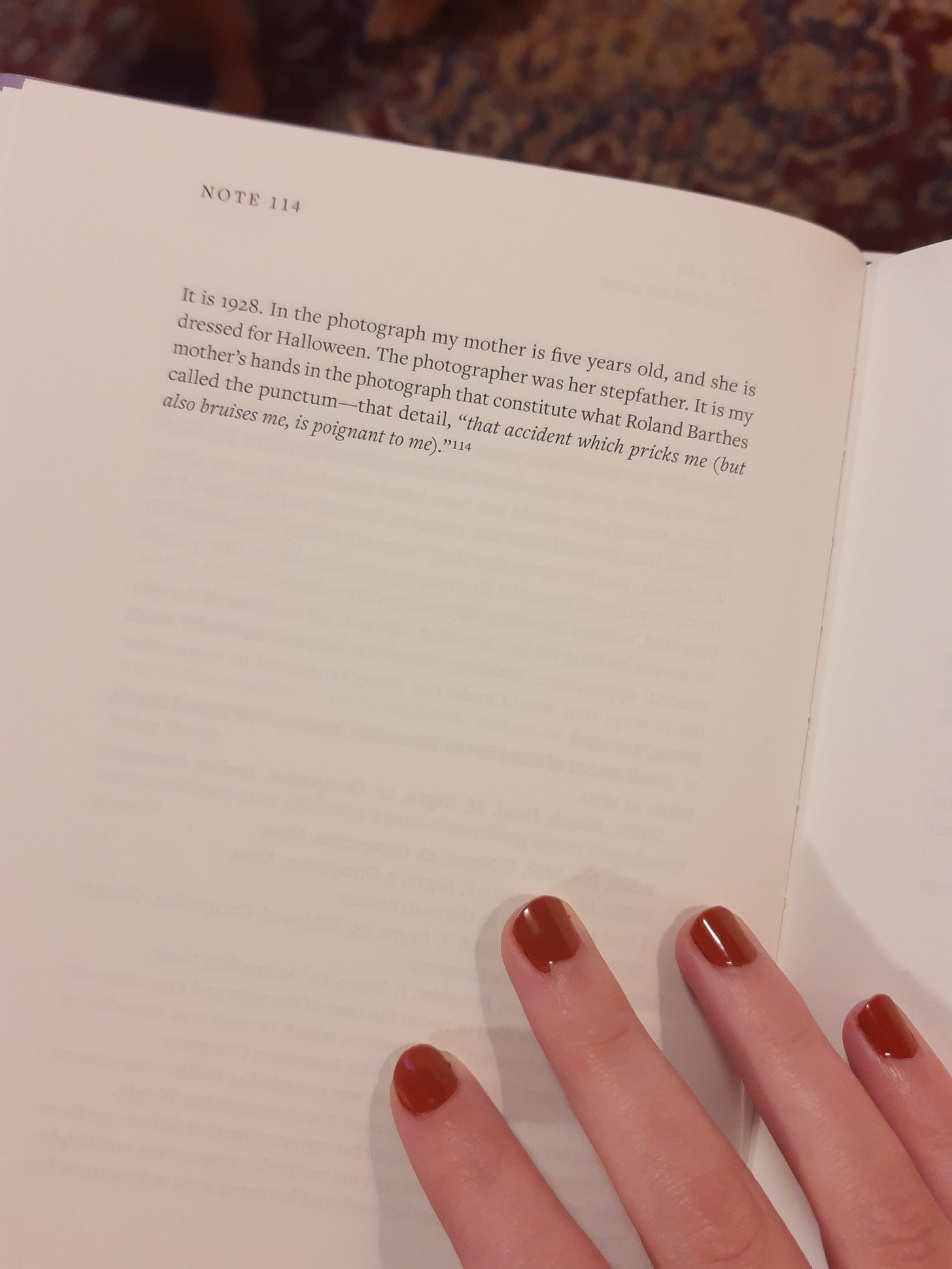

As the year wound to a close, I lay on my parents’ couch, flipping through Saidiya Hartman’s inspiring and incisive speculative histories of lives typically overlooked. Beautiful faces stared at me through the archival photos reprinted on the pages, fuzzed out by the blur of long-replaced printing processes. Most of them now more than 100 years old.

As a kid I used to be anxious about what I might leave behind, whether some kind of accurate portrait of me could be accrued from the detritus of my life—bad disposable-film photos of me with red eyes, mostly-empty diaries with only a few entries. Now there is a glut of information—data—about all of us available, though I suppose I care less now about being known and more about knowing.

Pictures of my great-grandparents and other ancestors—with their stern Mennonite scowls—always felt alien to me, almost like the people pictured were another species, and certainly nothing like the soft, laughing people I knew in their later years. In the less posed portraits in Hartman’s book there is a normal-ness that kind of shocks me—expressions, movements half-caught, ways of presenting that feel contemporary, despite the pictures being taken a century ago.

But every year, it’s a new year. And we take the same pictures and kiss at midnight and sing the same song that no one knows the words to. I’ve flipped over a new page in my new 2024 agenda, written the title across the top: books I’ve read this year. It’s blank, so far.📃

Other Links

My friend Alanna was one of the winners of this year’s Room Poetry Contest, and her poem is so, so gorgeous! You can read it here!

Aaand my friend Bronwen is starting a really cool coaching service for writers! Check it out!

Here is the Mosab Abu Toha essay mentioned above.

Also Martha Baillie’s essay, “Her Body,” is on Brick’s website.

I just read this haunting and moving piece by Patricia Lockwood, which is ostensibly a book review, but is more a meditation on the life of a friend who died and the grief of that friend’s partner, who wrote the book about her. It’s heavy, but lovely.

I’m not doing dry January but I am getting kind of into mocktails because I need something fancy to drink while writing during the day so that I don’t just pound six coffees in a row. I’ve been entranced by the mocktails on this account lately.

This was the kind of book that sent me to reading reviews to see whether I was alone in my distaste.